Michal Rovner | The Call Of The Night

Words are not trustworthy companions while traversing life on this old planet.

Some situations, encounters defy articulation. Words fail, most often when they are most desired – while hoping to describe a reaction to nature, while wanting to share a convoy of difficult emotions, while encountering overwhelming experiences. Among such examples I include the wild call of the jackal, a sound as if from back in deep time.

Michal Rovner’s video and photo works on these animals of the night, when I first saw the images, were a visual articulation of this failure of language.

The Israeli artist’s series on jackals that made up her solo show Night at Pace Gallery, New York in 2016 was not only a departure from the human figures – genderless and sans identifiable characteristics – that have populated her art practice for decades, but also, a work of immense personal importance to her, she says.

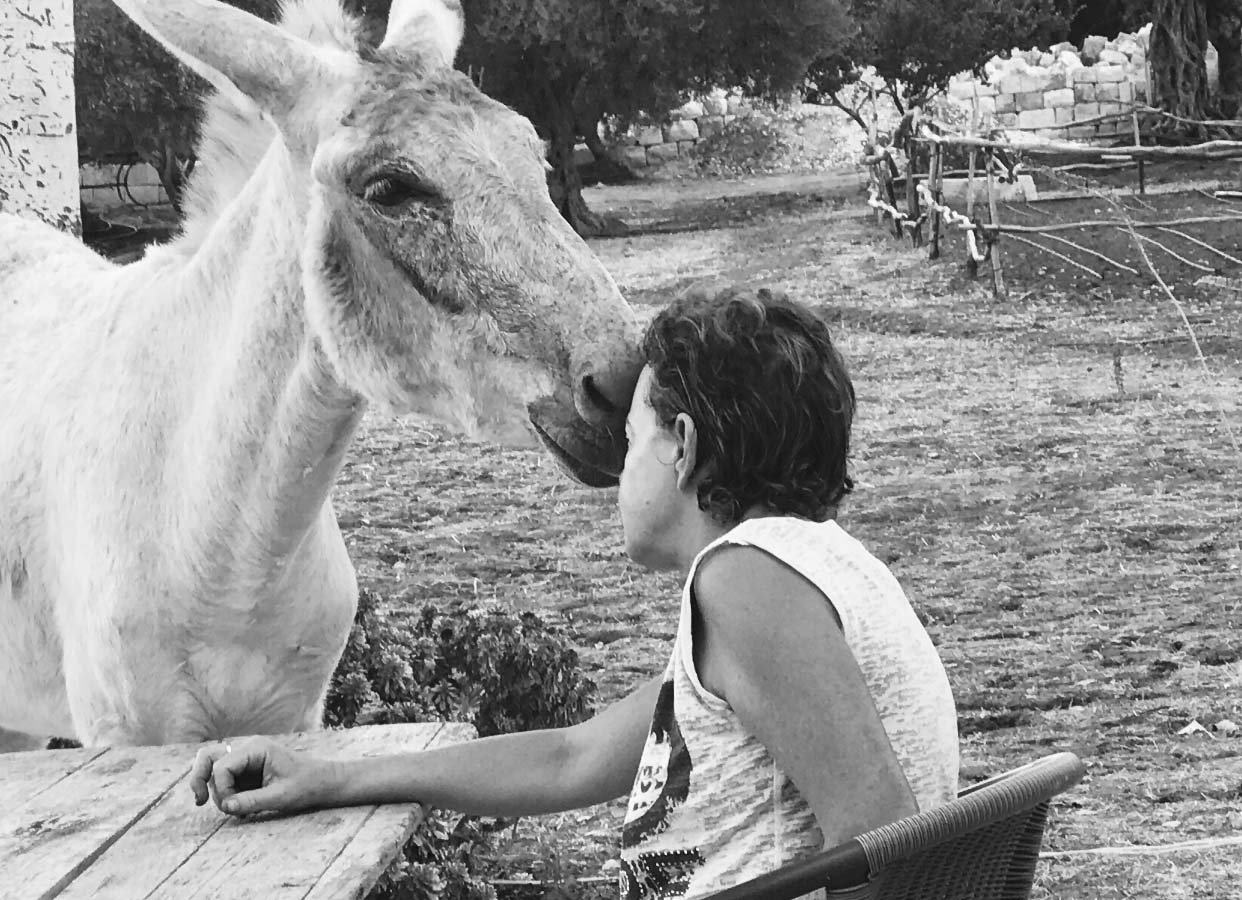

This phone conversation is conducted between two countries – Israel and India – and from two farms – hers, “midway between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem” and mine in a hill station in southern India. The freewheeling conversation begins with notes on these animals: the three wild “completely not domesticated” Canaan dogs (an ancient breed of canines that have roamed the desert since Biblical times) she rescued from the desert and the donkeys, one named Nohf (meaning ‘landscape’ in Hebrew) that she talks about elsewhere. We speak about India, about mysterious connection to places and landscapes, the notion of dislocation and Afghanistan. The jackals will come in later.

Michal Rovner’s works, right from the early photographs in the Outside (1990-91) series, to works like Time Left (2003) that was part of her mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York in 2002, to her 3 part solo show at the Louvre (2011), to her various publications and artist books, to Culture-C1 (2021) on show at the 17th edition of the Venice Biennale’s International Architecture Exhibition, have always taken an abstract approach to human conditions in the world. Only some projects, like Traces of Life (2013) and Living Landscape (2005), both responding to the Holocaust, take a direct, detail-laden approach, befitting the gravity of their historical context.

The vast majority of her work do not carry the burden of narratives. They do not carry specific stories or names or dates or such other marks of human history and existence. But precisely because of this lack of details, her works speak to the universal, and therefore the timeless – we encounter the art with our own lived experiences, and therefore it is continuously anew. They have been viewed and interpreted variously as expressions of conflict, dislocation of people and ideas, movement of memories, the cyclical nature of history and even as playful, poetic interventions. They conceal specifics to reveal something. In her four+ decades of career, Rovner has used various media to compose works that sift through nearly the whole gamut of art, from video and photography and sculpture, to cross-disciplinary interventions with music, architecture and writing. Not to mention a ‘collaboration’ too, with the jackals.

Rovner’s practice has always been prolific, evidenced by 70-something solo shows around the world, dozens of group shows, several books and public projects. And it is impossible for me to even touch upon the many, many things I want to speak with her about. Our conversation instead veers over broader themes, ideas, many stories. And notes on the jackals, of course.

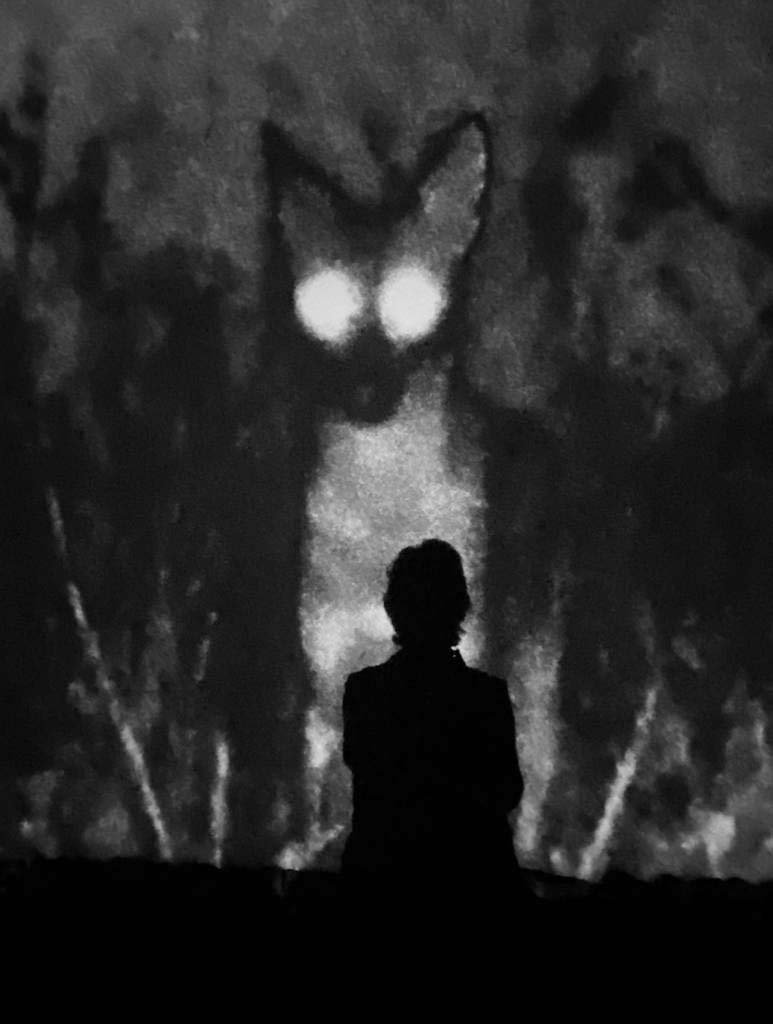

Michal Rovner, Night - 7, 2016, archival pigment print, 52-1/2” × 42-7/8” (133.4cm × 108.9 cm), Edition 3 of 7, Edition of 7 + 2 Aps © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

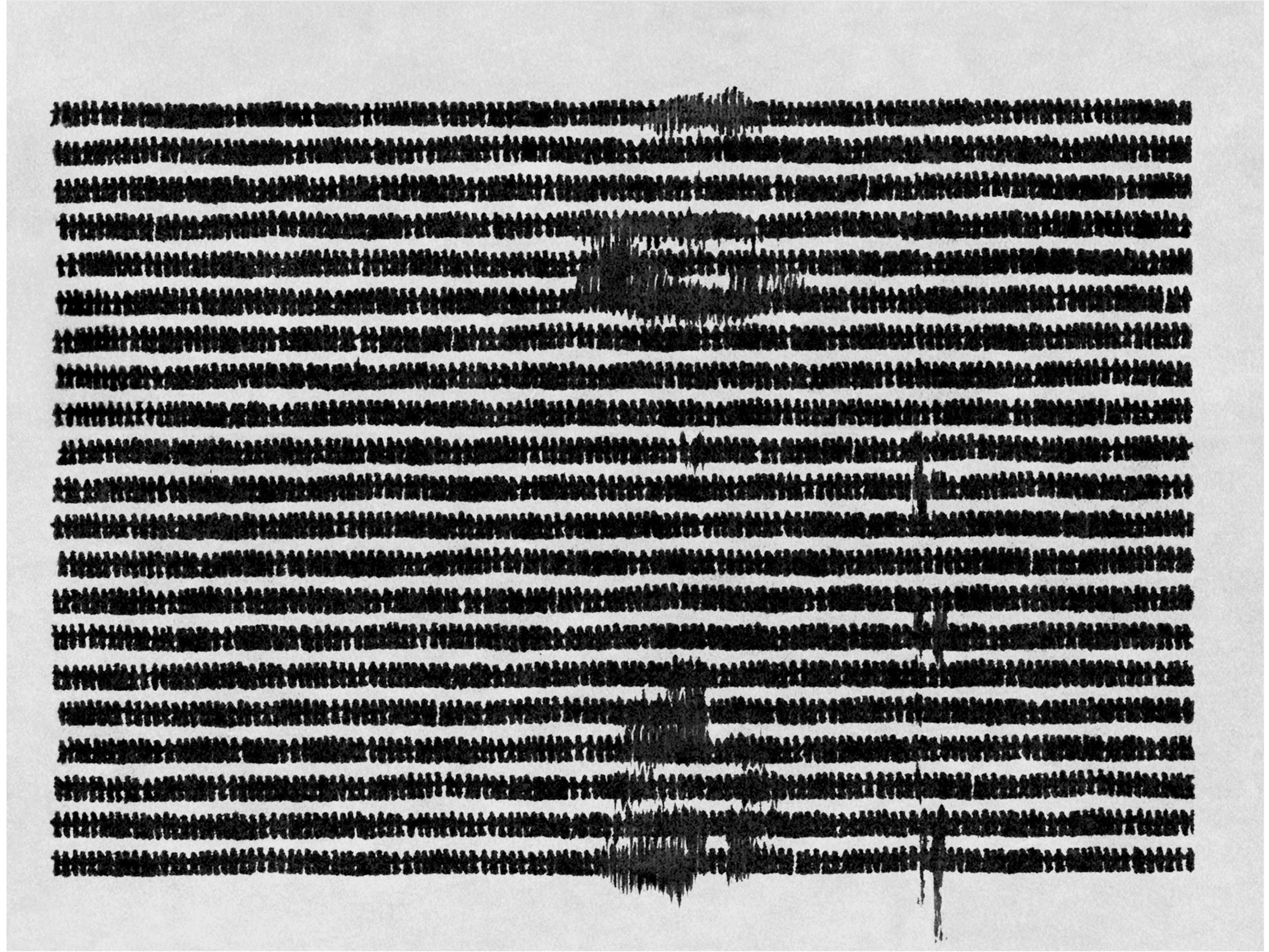

Michal Rovner, Time Left #1, 2003, pure pigment on archival paper, 30-1/8” × 38-3/4” (76.5 cm × 98.4 cm), Edition 4 of 6, Edition of 6 + 1 AP © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

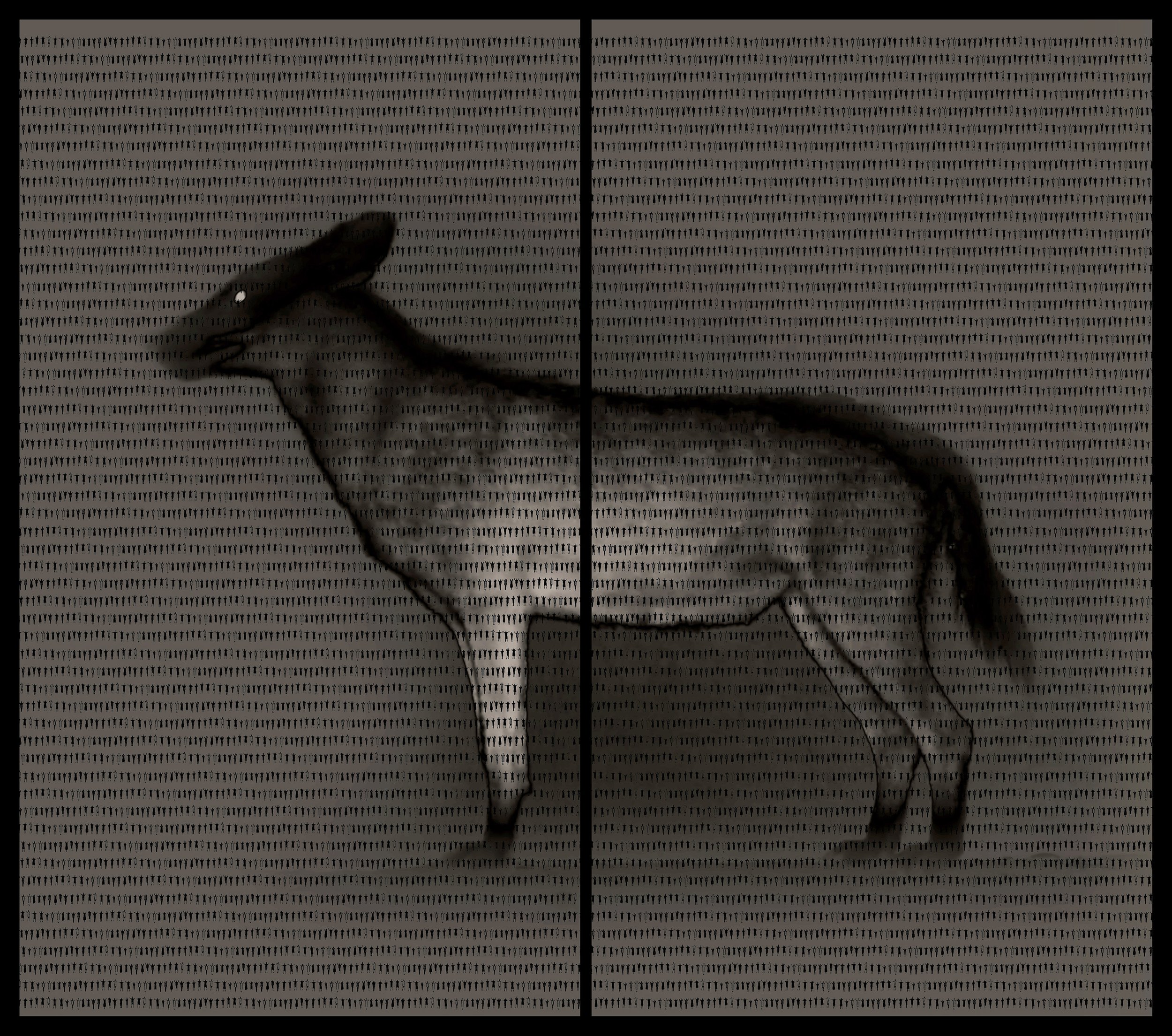

Michal Rovner, Culture-C1, 2021 © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

It is year two of the pandemic. Rovner, who lives between Israel and New York, tells me that she was super lucky to have spent the lockdowns in her home country, on her farm. “If I had been in New York, it would have been horrible,” she will tell me towards the end, before we say bye-bye.

Are they us? Are they them?

Not that any of us remained untouched by the shadow of the novel coronavirus. The notion of dislocation and people and places shifted is present very much in her work, Rovner says. “I am looking at pictures from Afghanistan (during US withdrawal from the country), people desperately trying to escape, climbing on the wings of airplanes, and the airplanes take off, and then to see those tiny marks falling, and the moment the realization of what you see hits you. These are real people, and then you sense that you cannot stand on stable ground. This is what you are exposed to, this is what is going on in the world now,” she says.

Rovner’s most recent work that is on display at Venice is especially relevant in the backdrop of such instable global conditions. It is a revisiting of the themes she explored in Data Zone (2003), her installation at the Israeli pavilion at Venice Biennale in 2003. The earlier work presented “large tables with petri dishes and inside there were tiny human figures. I called (them) culture dishes.” Tiny human figures, genderless and denuded of all identifiable ethnic, racial and biological characteristics – a motif that has become a signature in her works – came together, moved apart and came together quietly in varying patterns within the culture dishes. It gave the viewer the viewpoint of scientists, illustrating a laboratory. “At that time for me, it was (about) order and disorder, about human dynamics, the tendency to follow each other, the notion that we are part of a pattern,” Rovner says. Extending the idea, her new work, Culture-C1, presents red and white human figures moving in a chaotic but choreographed pattern on a black circular background that is reminiscent of a petri dish.

Michal Rovner, Data Zone, Cultures Table #3, 2003, steel table, six Petri dishes, four monitors and video, 2’ 9” x 9’ 10-1/2” x 2’ 7-1/2” (83.8 cm x 301 cm x 80 cm), Edition 2 of 3, Edition of 3 + 1 AP © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Knowing as we now do what the coronavirus looks like, the work acquires an amplified harsh reality. “It is almost like these figures that were in the petri dishes ran out of the little petri dishes. It becomes an image of, from a distance, of what we are going through in the world. There is a sense of instability and of unpredictability and the lack of control we are all facing. I think of the new expression that came in this period of time – we are all one humanity,” Rovner offers. The people in her works are all real people, filmed in real locations and not computer generated, as some might suspect. She is often asked, she tells me, who these people are, whether they are us, or whether they are a more vaguely understood ‘them.’ With Culture-C1, Rovner adds, “...it is clearly us, it is clearly the situation we are in.” Likening current affairs to a big storm, made up of a potent combination of the climate emergency, change of governments and decreasing democracy across the world, she calls it a storm that is on many, many levels. “We are exposed to what we are doing, what is happening. We are in that storm, we cannot look from the side anymore. We cannot even have the viewpoint of a scientist looking at it, even scientists are in it,” she adds.

Michal Rovner, Nilus, 2018, 2 LCD screens and video, 57-1/16” × 65-3/8” × 4-5/8” (144.9 cm × 166.1 cm × 11.7 cm), Edition 3 of 5, Edition of 5 + 2 APs © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Michal Rovner, Nilus, 2018, 2 LCD screens and video, 57-1/16” × 65-3/8” × 4-5/8” (144.9 cm × 166.1 cm × 11.7 cm), Edition 3 of 5, Edition of 5 + 2 APs © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I am the tree. I am the house

The human figures that Rovner uses to populate her works and to raise questions of movement and dislocation are all real. She films them in various countries and

locations. Some videos include her as well. While questions of ‘Us or them?’ are frequent in an examination of her art, I wonder how she sees herself in relation to the people she films. Is she a part of the mass? Or is she too filming a ‘them?’

“I feel it is both,” she replies. “When I film a tree, or when I film the house or animal, I am the tree. I am the house. I am the animal. I am so much in it, that I draw into that entity, to really dig into it.” But at the same time, she adds, there is a distance, a drawing back from the object. “I have to pull away in order to look at it from a distance. There is often a question, whether you see reality better when you are close to something, when you bring out all the details. For me it is often the opposite.”

Rovner proceeds to say this, about perhaps the most important note behind her art: “…On one hand I always start with reality, I always record reality. But then I erase the details. It is very, very important for me to map or detect something which is underneath the details. People want to get near to something, get more details and need to know more information. For me, very often, details are a form of blindness. They keep you on the superficial thin layer of what is actually going on.”

And then, “It is the tension between something that is real taken from a specific place, and you can feel it in the body. At the same time, it is very, very stripped down. It is real, and it is not real, and it could have been a reality that has to do with us. This is one of the questions (in my works). These people, these non- specific people, do you feel anything for them? Do you feel that you have anything in common? Can you care about a non-specific person?”

Michal Rovner with her donkey Nilus, Israel, 2021

Reduction and reduction and reduction

When Rovner erases specifics from the human beings she films, she is always looking to go to the very core elemental thing, the story under the story, so to speak. “I often try to see how many pixels you need in order to identify it as a person…I am always looking for the non-specific person. All these questions that we relate so much to reality, in the sense of where is it and who is it…I try to keep these questions alive.”

The chief query is whether it is possible to feel anything, something for a person if one does not know the figure’s narrative, details of name, place, family, origin, story and so on. Rovner mentions Afghanistan again, the horrific images of people desperate to leave the country is only a day or two old when we are having this conversation. “(The images) couldn’t be more minimal, couldn’t be more remote, unidentifiable. And it is so scary and it cannot not touch you. I am utterly interested in these kinds of images,” she tells me.

How to feel human emotions for human beings you know nothing about? The answer lies at the core of what it is that makes us human, if at all.

Rovner’s interest, from her early works onward, has been about “reduction and reduction and reduction.” She confesses to not having “very much patience for details, for dates and details and names. I am really trying to detect something that is underneath all of this.” An older example she offers is from the first Gulf War in the early 1990s. It was perhaps one of the earliest wars to be televised to a great extent. Rovner remembers watching it on the TV from New York, where she had moved by then. While worrying about her family in Israel, she sensed the very seductive, abstracted, pixelated, flickering reflections of reality. “The images were so gorgeous,” she says, “I was fascinated by the gap between the way they looked and what war is actually about.”

Rovner’s fascination lies in the way in which ‘real’ images unveil reality. “If you relate or don’t relate (to the people in the images), what is your ability to confront the reality you are looking at?” she questions. When the second tower fell on 9/11, she was watching it from the roof of her New York studio. Speaking of the screams of the city, and the silence that followed, she moves on to wonder this: “How much noise there is in our lives! And it is getting worse. There is no moment for silence. Communication is flooding our cellphones – Facebook, Instagram. The screens are always split to contain parallel sources of information. We feel we know at any given moment what is going on in the world but there is another world out there and that world is another reality.”

Michal Rovner, Tablets, 2004, two stone tablets, sand, two DVD video projections and two-channel audio installation dimensions variable © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Above: Michal Rovner, Broken Time, 2009, stone with video projection, 78-3/4” x 86-5/8” x 27-1/2” (200 cm x 220 cm x 70 cm) © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A very primal state of mind

I find it rather moving that Rovner’s works move away from details, eliminating the barriers of time and place. Here we live in an age of hyper-documentation, of a ‘me- me-me’ social mediascape where if something did not get posted, tagged or published online, it almost did not happen. It is interesting to juxtapose this modern urge to hyper-document with Rovner’s erasure of her subjects. There are, in her works, indiscernible landscapes and hazy, dreamy backgrounds, apart from the human figures. The deliberate ambiguity probes into evocative memories. It is conducive to emboss one’s own sense of personal histories on her situational works. Elsewhere, she has talked about being interested not in the memory that has to do with remembering, but more with the residue and the leftovers of events on the mind, with the mark that is left.

Rovner is not a participant in the social media world. But she acknowledges that the ‘me-me-me’ culture is about an ancient urge to leave a mark. When human beings come across things of wonder or fear or magic or similar heightened emotions, the first instinct is to share. “To imprint something, to recast reality or an object or a form, to send communication.” Speaking of cave paintings as examples of the very human urge to both leave a mark and to communicate, even if the recipient is unknown and unimagined, she adds, “There was always an urge to pass it on, that kind of passing on of experience, of reality, of what you found out about reality, your own geo-point of reality, (your) own touch with reality. I think this is a very primal state of mind.”

This harking back to early humans is extended in her works with stone, for instance in Broken Time (2009) and Tablets (2004) where the projection of tiny human figures is, like she says, “…bringing back the old desire to imprint on stone, something that would be stable, be kept in a safe place, to engrave. We have the process of time, the residue of time, the erasure, the forgetfulness, even sometimes denial, the missing information. At the same time, we are in reality, we are trying to hold on to reality but it is very temporal, very instable. Now it is becoming more and more instable. It is shifting under our feet, the flux is so strong and there is a desperate desire to leave a mark.”

Rovner tells me that she understood the urge the first humans must have had while filming the jackals. “The awe and the kind of revelation you have when you have a jackal coming and sitting next to you and looking at you…and I said (to myself that) I feel like the first man who wanted to run into a cave and I wanted to make a drawing or a print or to keep it, keep that moment, that kind of magic…the very basic urge of art is, I think, the same urge, the way you relate to reality. You want to create another reality, a parallel reality. You want to change it, you want to rearrange it, you want to feel like you have some kind of control over it.”

As artists, creators, as people coursing through layers of reality, a lot of our decisions tend to hinge on the illusion that we have some semblance of control in and over our lives. But the collapse of many established systems in and around the year 2016 led Rovner to make one of her most celebrated works.

Night, a series of video portraits and photographs of jackals.

Michal Rovner, Anubis, 2016 © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pièce de résistance

Jackals (Canis aureus) do not often get good press. In many cultures, they are seen as cunning, opportunistic scavengers and used in reverse anthropomorphism to refer to shrewd people who are to be avoided in polite society. But for the Egyptians, jackals are Anubis, the god that guides a soul from life to the afterlife. Jackals live on edgelands, not quite within the city, but neither entirely within the depths of forests. “They could be a few meters from you and you wouldn’t know it,” Rovner tells me.

The wild call of the jackals was familiar to Rovner. She tells me that every time she hears them at night, she goes outside. “I am very drawn to their mysterious, strange voices, like sounds from hell. It is so powerful, like another music,” she says.

I am nodding furiously on this end of the phone line. The hills behind the farm where I grew up were once filled with jackals, and their ancient calls into the night were the soundtrack of my childhood, I tell Rovner. I no longer hear them because of rapid urbanization, but I am certain they are not too far away. Perhaps this is why I am intensely drawn to her jackal works – evocative memories, in lieu of hearing them on deeply dark nights.

She talks about how back in 2016, there was a great deal of dislocation in the world, especially with the refugee crisis seemingly at its peak. People in movement were treated with suspicion, as strangers, as problems that needed to be wished away.

When the whole world map was shifting thus, Rovner decided to sit in the dark because she says that she felt like it was a period of darkness in the world. Here were people who suddenly did not seem to count anymore, “faceless people walking in endless trails through the deserts, on boats through the seas.”

This is why she wanted to work with nights: “I decided to sit in the dark field because I also wanted to have the sense that I don’t really control what I am doing. I think for that, this series is really, really important for me…to make good art you need to (be) really brave not to control something too much, to really give in to whatever happens.”

Michal Rovner, Night - 1, 2016 © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Michal Rovner, Night - 2, 2016 © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

She sat at the end of her field and in other locations for days, for months. For the jackals, she was the stranger, the intruder in a parallel dimension of existence, just like they were strangers and alien to her. Filming them with conventional tools wouldn’t work because the light would chase them away. “That pushed me into (using) another technology all together, which is very, very interesting for the form and content. I had to use infra-red surveillance equipment,” she explains.

And then it happened one night that a jackal came out and into her line of vision. Rovner calls it a very moving experience. It was a female jackal, possibly with kids. “She looked at me. She looked at the right and left, was very alert. And then she ran away. And then she came back and ran away, and came back and ran away. When I put my hands to the camera, she ran away completely and then when I sat quietly, she came back again. And then she lay down,” Rovner recounts. She remembers having the old feelings about cave paintings and stories from mythology. She remembers an old trip to Egypt with her parents where she saw and was mesmerized by hieroglyphics that contained images of jackals. It would be many years later that she would learn that they were images of Anubis, the gatekeeper, the guardian who accompanied the souls to the afterlife.

These surreal experiences led to the works in Night. Rovner blurs out the details in most of her works to free them from being reduced to easily readable narratives. But she told me that the only real portrait she has made in the last two decades was that of the jackals. “The (little figure) humans…it is more about humanity, it is not about a specific person. But there, (with the jackals) each one was an entity by itself.”

Michal Rovner and her wild dogs, Israel, 2021

One of the works, a video projection titled Alert (2016), is especially important to her, she tells me. “…it was one jackal with the white eyes from the infra-red (camera) that I amplified. And behind him I put a landscape that looks like a view or a map of the world we live in, with a lot of tiny little people moving but really stuck. They move but don’t get anywhere. They try to hold hands. It was almost like the jackal is looking at us, at what is going on with our reality (in) these times,” she tells me.

Anubis (2016), a large-scale installation in a cave-like room, had jackals she filmed being projected on the walls. There was very little movement of the jackals. “In that zone, it was kind of like you look at them and they look at you. There is a feeling that there is something behind them, that they are guarding some kind of an invisible threshold,” Rovner describes to me. I was not lucky enough to see the show myself and rely on her words and documentation of the works. But the experience of the show has been variously described as eerie, surreal, moving, affecting. I can well imagine.

Jackals are known, including in the Bible, to come to cities that are deserted, burned. They come in when the people are gone. The works in the Night series took on a new relevance in these pandemic times when cities under lockdown saw jackals, among other wildlife, come out in the open. “This is like the way nature came into our cities. In the lockdown, people started to see them. But also, other animals came…to be reminded that…we are part of nature. We cannot forget that we are part of nature,” Rovner says.

Michal Rovner, Alert, 2016 © 2021 Michal Rovner / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

History began when writing began

Just as spoken words might fail, so does language in writing.

The visual language of writing has always fascinated Rovner, she even invented a sort of alphabet with a friend when she was a girl. “I was always fascinated by text, by writing, the formality of it, the visual appearance of it, the act of writing, the way it is organized… But also, writing is a form of communication – someone writes and then there is the other person who reads it. You don’t know who is reading, how they are going to read it, what they are going to read into it. And the urge to actually write something, the urge to not only communicate but the urge to write our own experiences… History began when writing began,” she tells me.

She remembers being speechless when she saw the hieroglyphs in Egypt – there again, in her reaction, language’s shortcoming. The human urge to inscribe “our history, our realizations, our understanding, the way we understand reality, our viewpoint, our comment, our desire, all of that goes into writing,” she says.

Her ‘writings’ can be categorized to the genre of asemic writing – marks, words and paragraphs that retain the formality of written language but cannot be ‘read’ in the conventional sense. Yet, asemic texts have been described as the essence of writing that go beyond the constraints of formal language, instead, resonating with the potential for meaning.

Rovner’s interest lies especially in writings which are not very clear. “I am interested in the erasure, I am interested in writing that has been eaten by the residue of time,” she tells me. Keeping with her larger theme of going beyond blindness arising from details, she says that she does not find it necessary to always understand what is written.

“Very often I don’t ask what it is about, I just look at it. I am very moved by the act of writing, the very urge to write, the urge to communicate.” This led to her using her own figure in creating letters – some of them resemblance a few letters in Hebrew. Several of her ‘writings’ contain her own figure, she tells me, but emphasizes that they are not self-portraits. “I am just a human element who was there then.”

Naturally, the conversation segues into the state of writing by hand in this age of computers – about how writing is now in the binary language of zeroes and ones, how the slowness of writing by hand is displaced, about autocorrect and how humans themselves are being barcoded. “We are being barcoded ourselves, our communication, our text. I think it is very disturbing. We are losing some of our language, we are losing the subtleties even,” she tells me.

On one end is the illusion of progress and the control we think we have, as also, because of the internet, the illusion that we have access to everything and the ability to be everywhere when something happens. “But look at the degree of unknowingness and non-control going on in the world now, the instability, the flux. That is why we go to have a little bit of nature, the earth and the animals to keep our sanity,” Rovner adds.

Michal Rovner on her farm, Israel, 2021

This perhaps is the greatest takeaway from her works. That cliches like the healing in nature – we are part of the cosmopolitan nature, not a species apart from it – are truisms, even in the deteriorating world we are living in. That everything, everyone is deeply connected, whether such inter-relationships are acknowledged and understood or not. That ‘they’ are us, as too we are them.

Words by Deepa Bhasthi.

This story was published in noisé 01 The Solstice, 2021.