Roni Horn | Yes and No and Egghead

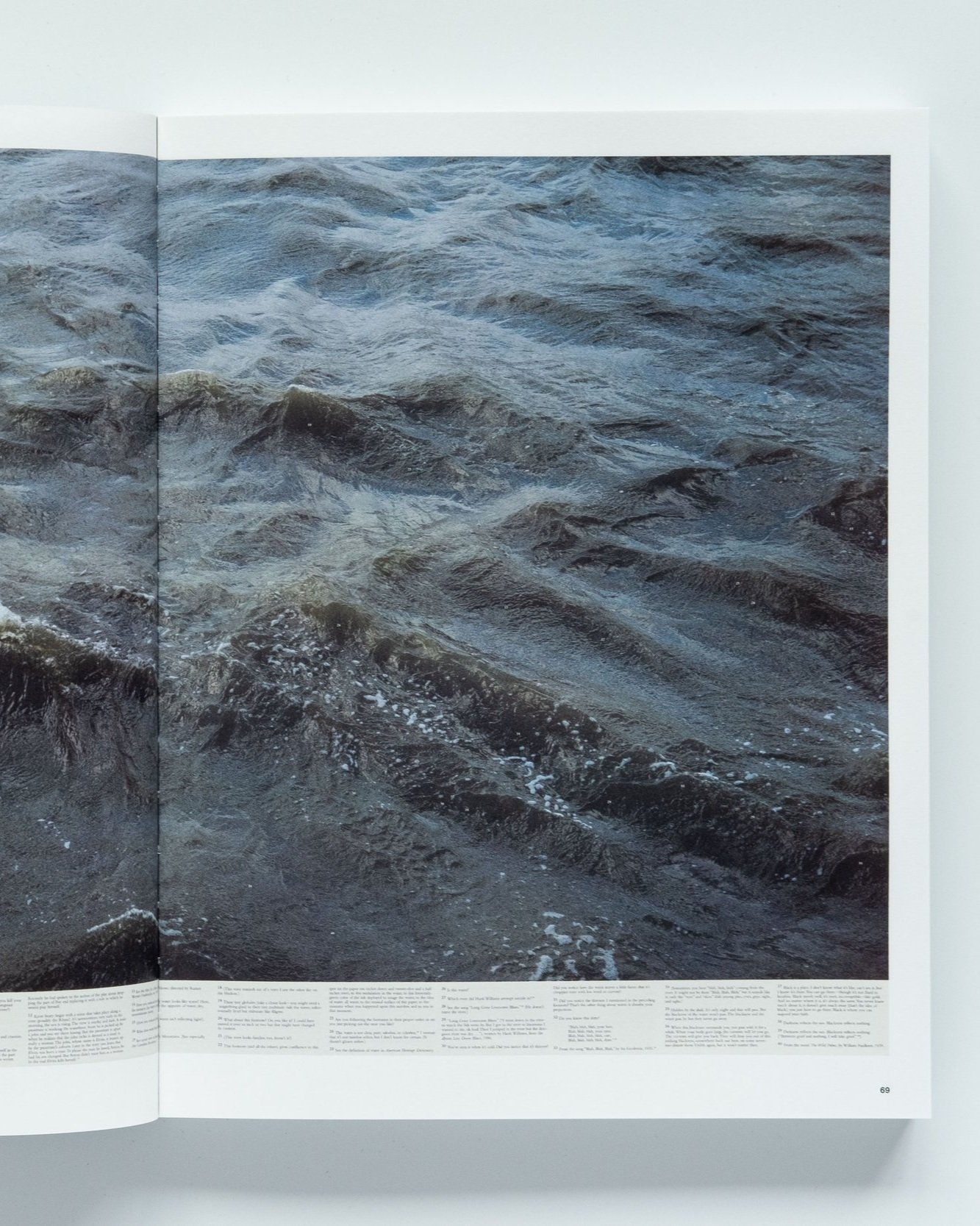

The conversation with Roni Horn happened during a week when I immersed myself in her past interviews, podcasts, and artist talks. She had just returned from Europe and escaped to Maine, where the proximity to the Atlantic Ocean shelters her from the sticky weather of New York.

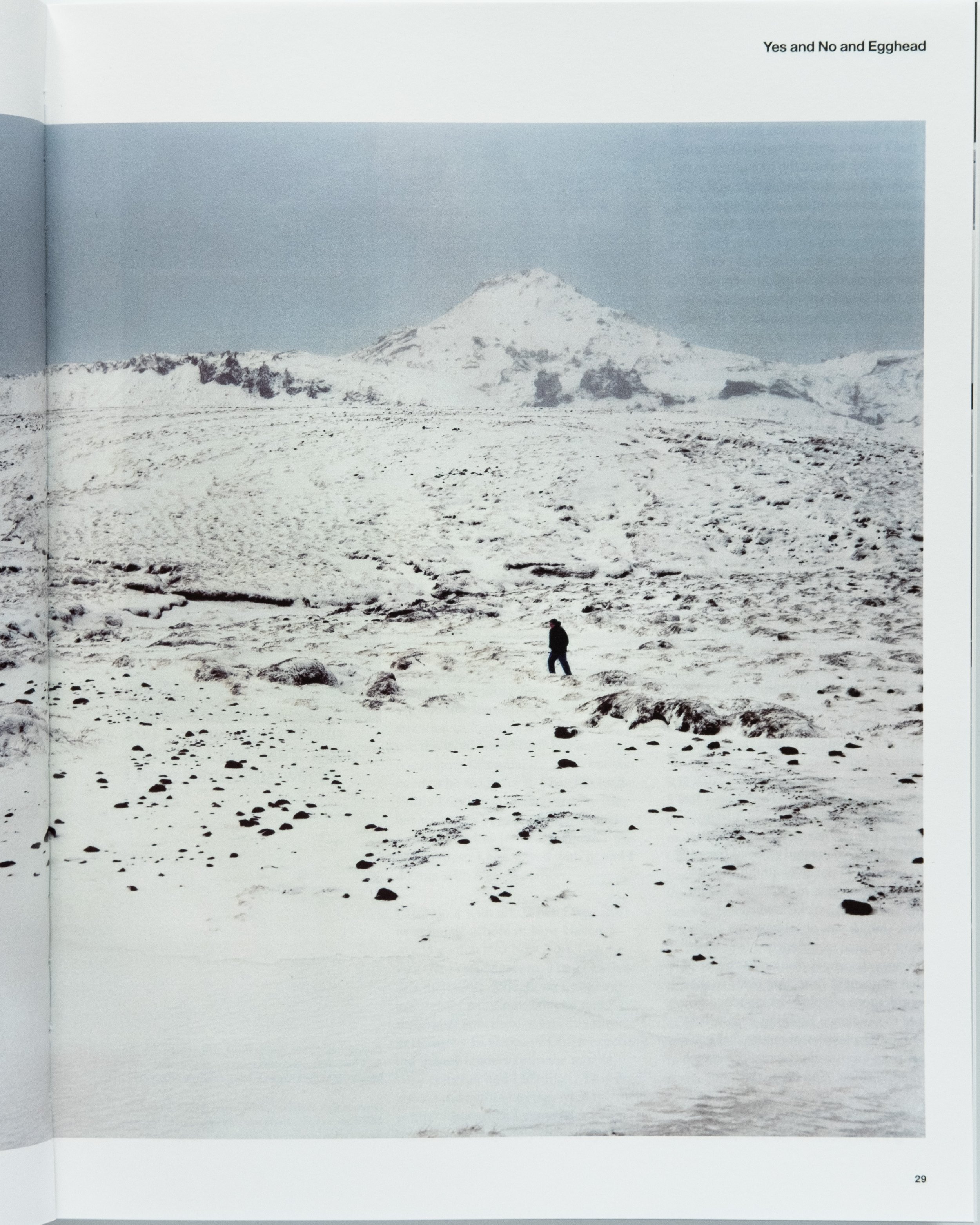

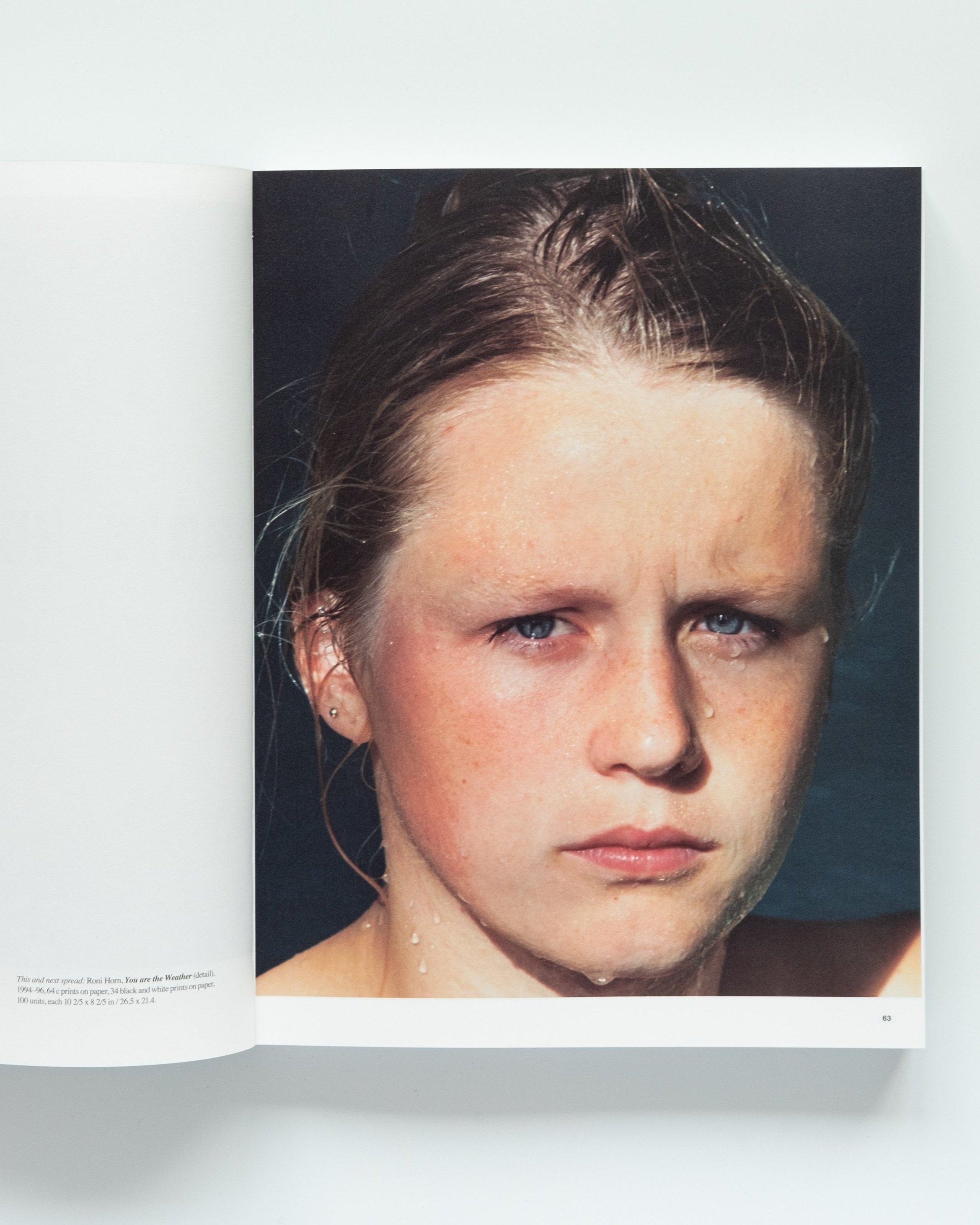

Understanding Roni Horn isn’t easy. Her persona doesn’t unfold through her multidisciplinary works or public appearances. Her photography, glass sculptures, poems, and even the titles of her exhibitions draw me closer, as if she’s passively yet vividly communicating. In one video, Roni was invited to share anecdotes about her project Weather Reports You in Iceland. She sat down, set aside her prepared notes, and began reading from a book. When an audience member coughed, and a door slammed, she stopped, glanced sharply in the direction of the noise, and rolled her eyes. She builds a fence against people, a feeling you naturally share if you see her eyes. Without delving into her art, she already feels like a paradox.

The urge to understand her and her work led me to compile a list of 20 questions that I shared with her before our interview. I received zero feedback. The anticipation was like Schrödinger’s cat until she appeared on Zoom with a warm smile. Her camera quality was low, but I immediately detected a fair amount of curiosity and expectation in her eyes. The cat was alive!

Our conversation flowed quickly and smoothly, magically deviating from my question list yet covering everything I sought to understand about her paradox. I had assumed her repetitive pairing patterns were intentional, guessed her obsession with water and Iceland had deep roots, and hypothesized her productivity came from life experiences. I thought she, of all people, could describe herself explicitly, given her solitary life. I gave her a hard time with this unreasonable test-like question, asking her to reduce herself in three words, and she responded with a simple, humorous answer that perfectly captured her character: “Yes? And No? And Egghead?”

Yet, astonishingly, she clarified the paradox of Roni Horn: there’s nothing oxymoronic about her. She is self-evident, like her glass work, like her retrospective Roni Horn aka Roni Horn. Once you know her, you really know her.

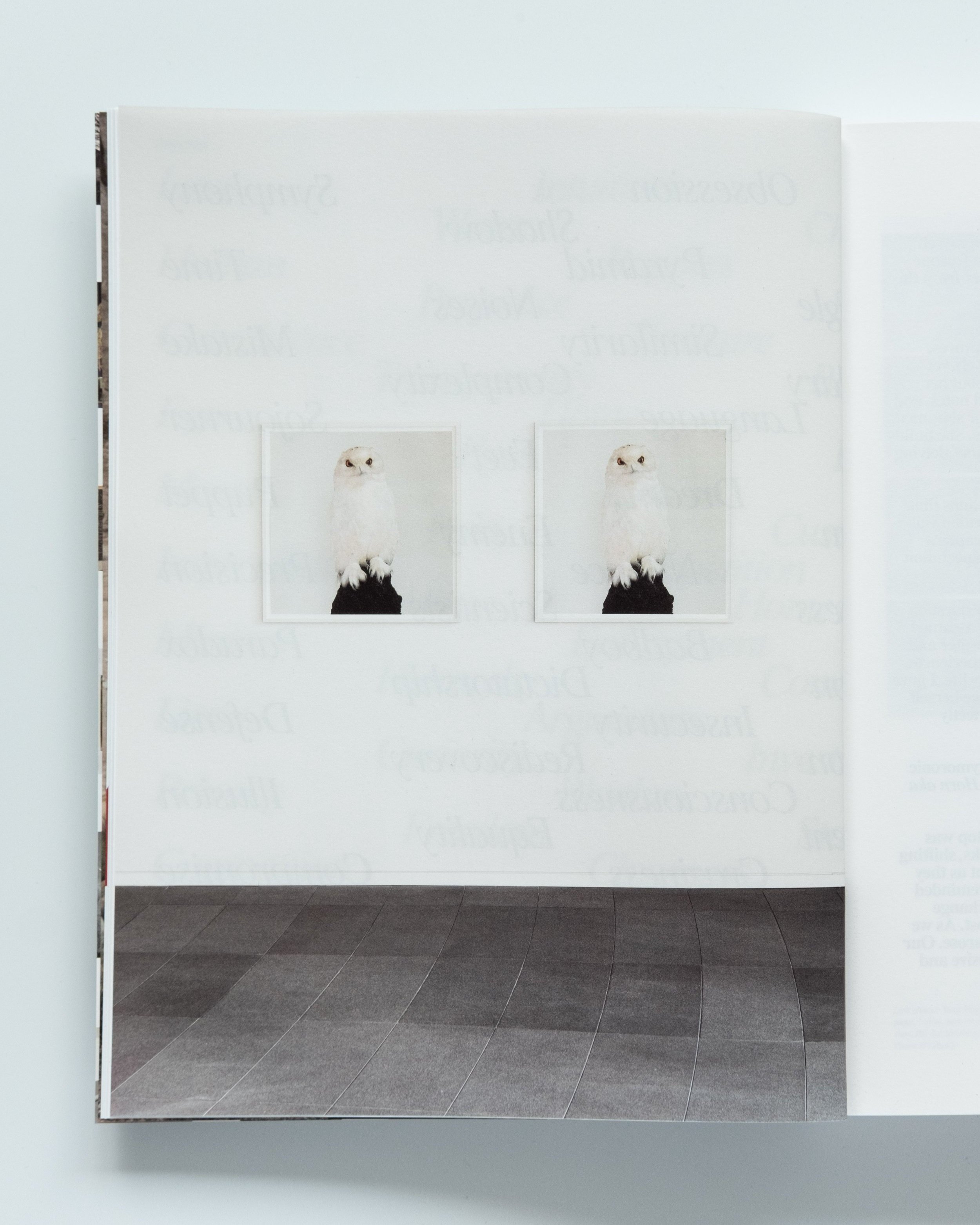

When I was sorting out our transcript and replaying the recording, my desktop was occupied by her double Dead Owl. From time to time, I felt their curious peeks, shifting from left to right and back again, their bright golden eyes humorously patient as they seemed to watch my every move. This constant, almost whimsical presence reminded me of my conversation with Roni. She allowed a space for expression and exchange without disguise; the smoothly evolving dynamic was humanized to the utmost. As we talked, we knew each other better, and with each revelation, more questions arose. Our conversation was just the tip of the iceberg; beneath the surface lay an expansive and intricate foundation, to be continued.

Murphy Guo: Hi, Roni. I’m Murphy.

Roni Horn: Hi, dear. How are you? Nice to meet you.

MG: Nice to meet you, too. I really appreciate that you can make the time for this interview; I know you have quite a busy schedule.

RH: Yeah, my pleasure. Thank you, Murphy. I have to say, some of your questions are quite fascinating and very thoughtful.

MG: Thank you. That means a lot to me. As you’ve gone through all my questions, I’ll just start from the first one, about the meaning of doubling and repetitions in your works.

RH: This pairing and doubling thing—thought plays a big role in my creative endeavors, but it’s not like I always know what I’m doing. I often feel it’s one long improvisation. It’s not as intellectual as it appears; the double or the idea of two, for me, always incorporates a third element. And the third element is what’s between the two. In sculpture, this was natural. The pairing thing really started in my practice in sculpture when I was in graduate school at Yale.

As far as I can remember, the first thing I ever did that was paired in a meaningful way, in terms of how I was working, seemed very elemental to me. This particular pair was for a graduate thesis show.

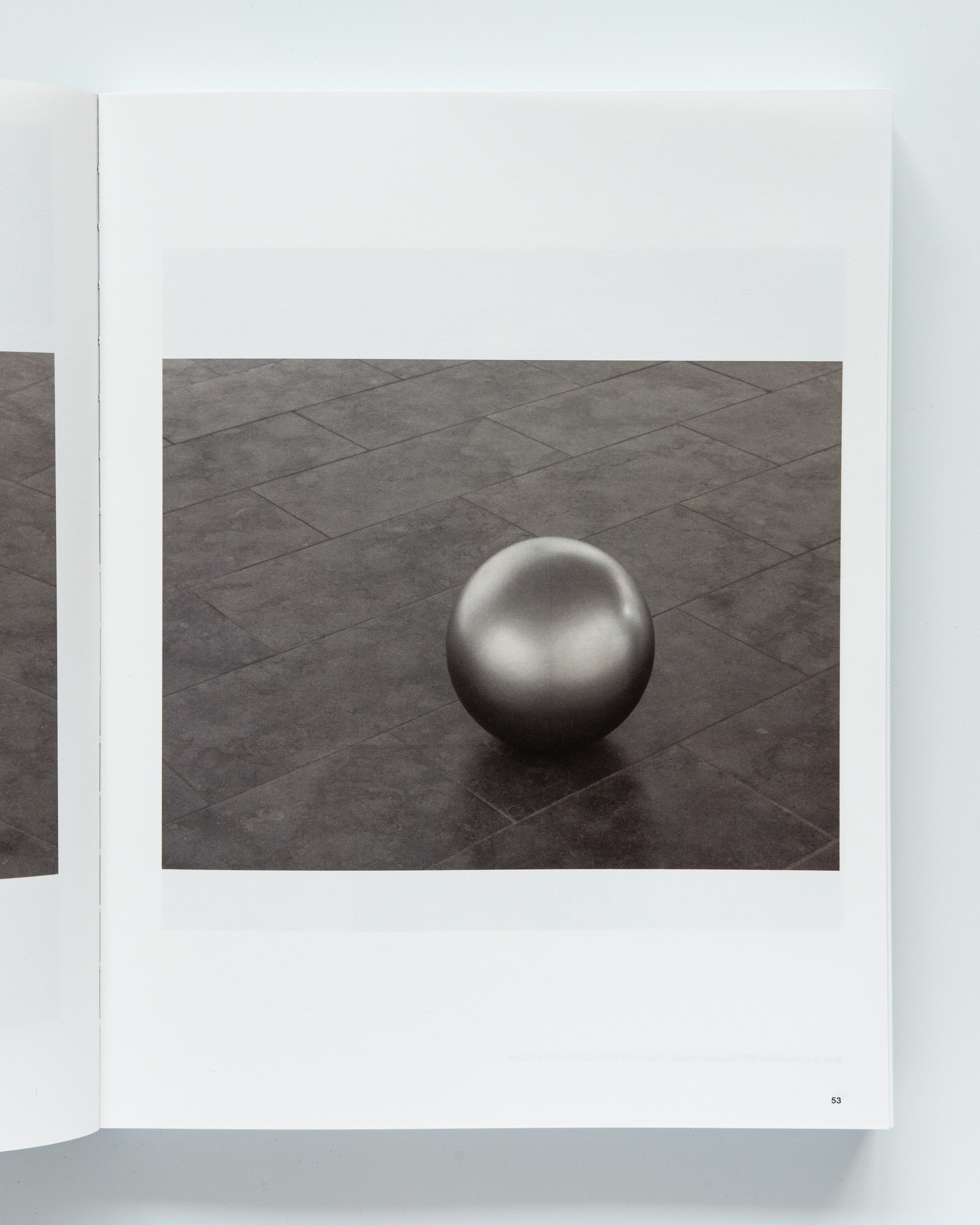

There was an art gallery in the art school, a large space, roughly 500 square meters. It was divided into three rooms symmetrically. You entered the first room where I placed one object. Then you went to the second room, which was the main space of the show. I left that empty. In the third space, you found the second part of the pair. That was the first time I recall using the double. It stirred up a lot for me because leaving the main space empty was obviously counter to the basic expectation of gallery space. It made the emptiness as important as the pair that held it together. That’s where it started, and it just flowed from there.

It seemed to be a natural part of my intuitive language to work in pairs. Even the big drawings started as two. I would make a drawing, copy it by eye, and then cut them together. Sometimes they would become one, or sometimes they would remain two, but always in a relationship that I developed.

I think with the pair, as with water, I kept rediscovering them. It wasn’t like I kept going back to this form or this subject. They would come back to me in ways that were different, ways that I was ignorant of previously.

[…]

Read the conversation in noisé 04 Prism Fall/Winter 24 issue.

Words and interview by Murphy Guo.