African Art | The Context Behind

WonderBuhle, Where I am from everyone is King, 2021, Acrylic and metallic paint, 34.25” x 29.92” (87cm x 76cm). © WonderBuhle 2020, courtesy Galerie Ron Mandos, Netherlands.

On May 16th, 2017, Sotheby’s inaugural sale of modern and contemporary African art sale fell slightly lower than the estimate (£2,794,750/£2,800,000), with most of the sold pieces unexpectedly surpassed their highest estimate. It’s a strong signal: the art market and collectors worldwide confirmed their interest in African artwork, loud and clear.

The exponentially increased demand from collectors has unsheathed the blade of the African artists in the public eye, leading to the netizens finally making it a trend. Thanks to social media and the cloud-based video conferencing service, we successfully arranged this soulful conversation between artists Annan Affotey, Lerato Nkosi, Matthew Eguavoen, and Wonder Buhle Mbambo with Makgati Molebatsi.

Makgati has quitted a 30-year career in Marketing and Communications and started her brave journey in art in 2016. As the senior art advisor and one of the co-founders of LATITUDES Art Fair, Makgati sees the gap, in another word, the invisible wall between the established art market and the South African art world, and she is devoted to breaking it down.

From what they have discussed over the 2-hour conversation, we get to know what we are curious about: how did they start their creative path? What’s the urge? What’s the message? How do they cope with the rising market? On top of that, we see the anxiety and the certainty, the depression and the faith, the disappointment and the reliance, which are profoundly and robustly connected with each individual, and with this continent, in which they’ve grown roots.

And that is never about the trend.

Lerato Nkosi, Restoration of Bonds, 2022, Ink and stamp on canvas, 130 x 90 cm. © Lerato Nkosi, courtesy Latitudes Online.

The Starting Point

Makgati Molebatsi

When I went to London to Sotheby’s Institute of Art, on the very first day, we were tasked with doing a presentation about an exhibition that we just saw. I remember it was a class of 36 students, and I was the only black person in the class and the only person from Africa. The presentation that I did was Somnyama Ngonyama, an exhibition by Zanele Muholi at Stevenson Gallery. I remember the lecturer and the students were looking at me with that blank stare, not knowing what I was talking about, not familiar with the artist that I was talking about, and that was in 2016. Four years later, Zanele had an exhibition at the Tate, and I wondered what my classmates thought of it.

Annan Affotey

I used to paint all around with a lot of different techniques. This new body of work started when my wife told me about her pregnancy, about our little baby. I used to live in Wisconsin, the United States—it’s very racist. Though I haven’t really experienced any of the racism stuff, we know a lot of things have been going on. I’m an artist, and I find it difficult to speak in public, and I’m kind of shy. So when my wife told me about this news, I was like, how do I create a voice as an artist and also as a father, also tell my own story through these images and through these characters—I have to create portraitures that look just like me, a darker skinned person. So that is how it started.

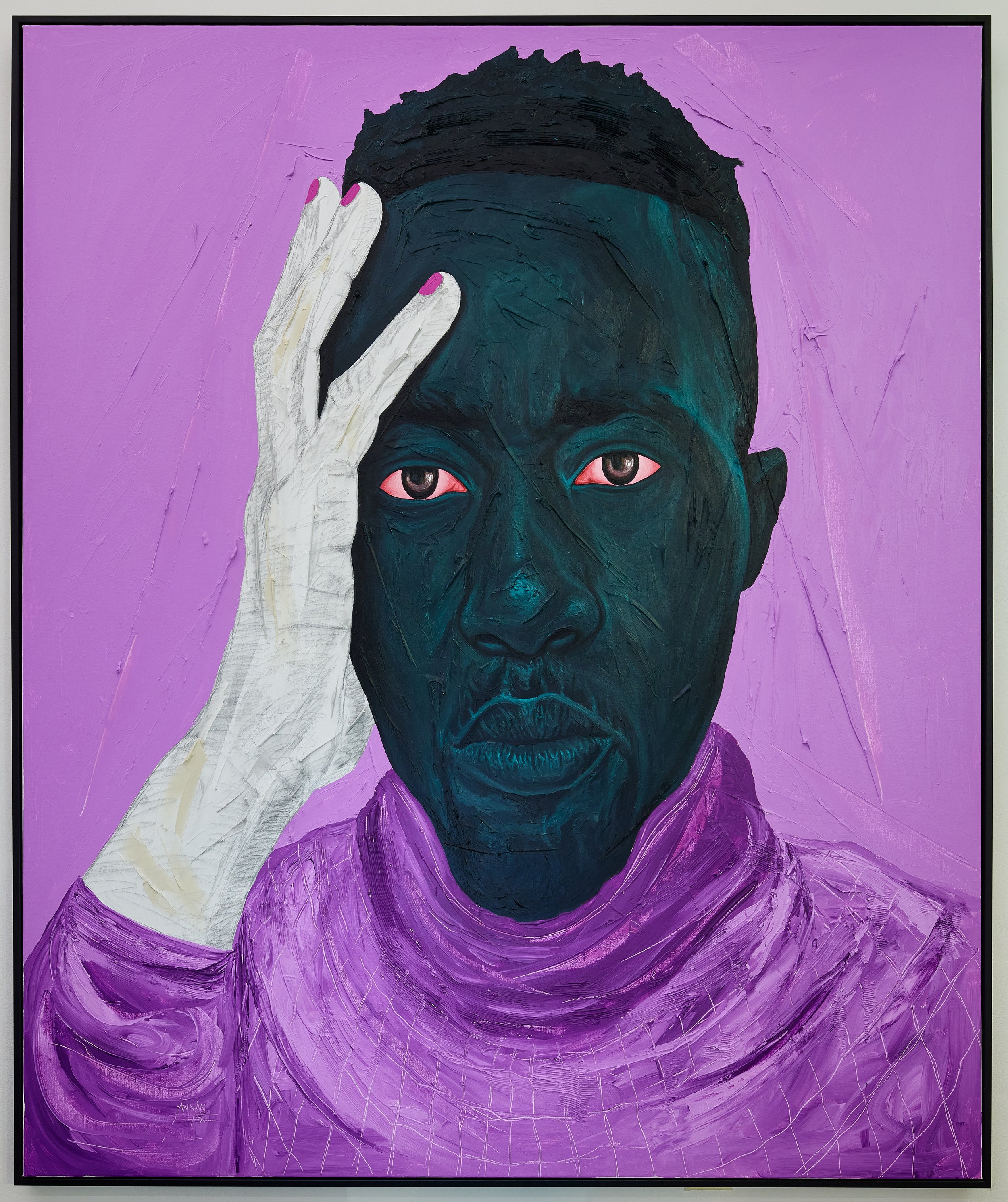

Annan Affotey, Deep Thought (Self Portrait), 2021, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 72 x 60”. © 2021 Annan Affotey, courtesy Ronchini Gallery.

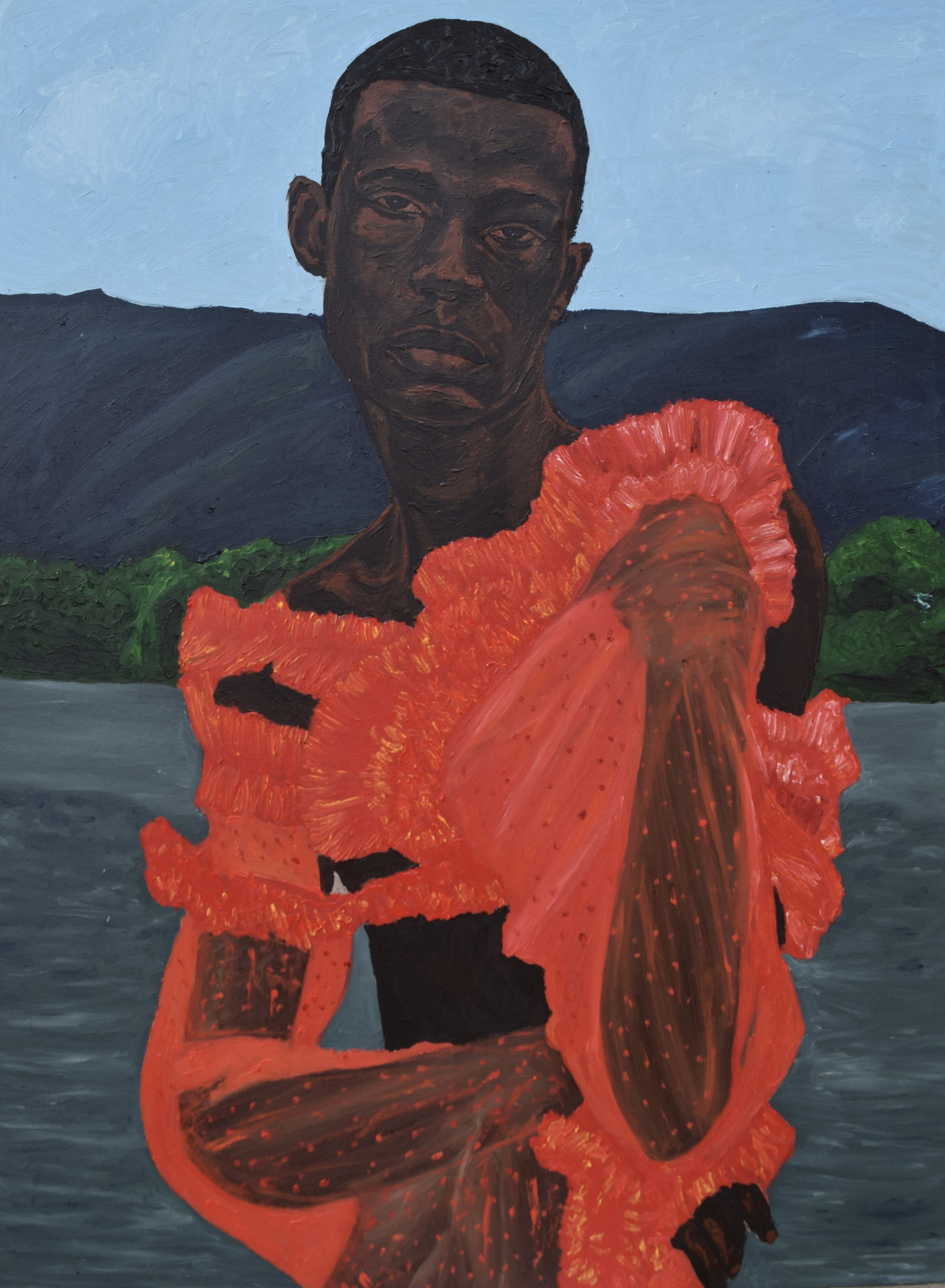

Matthew Eguavoen, This is the reality, 2022, 62.9” x 42.2” (160cm x 120cm). © 2022 Matthew Eguavoen, Nigeria.

Matthew Eguavoen

I think, first of all, we’re creating art. It doesn’t matter where we’re from or what continent we’re from. Why my work is about black bodies or brown skins is because I’m African; I’m trying to tell my story and the story of my people. I cannot be in Africa, creating in Africa, and then painting a different skin tone because I wouldn’t have that experience, so I wouldn’t have been in that place when it’s needed. Because I was born and raised in Africa, and I’m still here, I’m able to tell that story using my own color of skin. That’s why I do what I do.

WonderBuhle

I think right now, African art is one of the most fast-growing mediums of expressing ourselves and changing the narrative on a global stage.

I was reading something like two weeks ago, and a curator said African art is a trend, but I feel like we’ve all been doing this; it just reached the point where nowadays, there are media that can present us or show us in the world. I can show that I’m actually painting in a rural area in my country because I can use social media. But that doesn’t mean it’s a trend; it has always been there, only now, it is a better medium to show us to the world. So when the brothers are talking about representation and what it means to them, I feel, and I think, we are slowly dominating the Western culture in terms of painting. We are not really dominating in a negative way, but more like having an eye-level conversation with their ideas and what they are portraying about themselves. We also are able now to show our pride and the things that we represent.

There have been all these movements around the world where artists were painting the same subjects almost in the same palette. So now it’s us.

WonderBuhle, Isibindi, 2020, Acrylic and metallic paint, 87’’ x 63,77” (221cm x 162cm). © WonderBuhle 2020, courtesy BKhz Gallery, South Africa.

Lerato Nkosi

I remember when I was still in school, we used to wear white shirts. If you put your pen in the pocket of the shirt, the ink would damage the shirt. That’s where the concept of working with ink came from, like a stain that doesn’t come out once you have put it on a surface. What else works with the ink? It’s the stamps. For instance, you go to a police station to write an affidavit, and then the policeman stamps on it. You can have authority over any situation with that affidavit because it has a police stamp. So I use the stamps in that manner. I used to paint with colors as well, acrylics, I felt the works were quite empty. I started with this medium at a crazy time; it was in 2020 when everybody was just going through hell, not knowing what was going on and if we were ever going to make it out alive or not. I think I needed this because I was always made excuses for not painting, but once I held the brush, it felt like I was home again, and I think this medium is where I find myself.

Lerato Nkosi, Devotional Silence, 2022, Ink and stamp on canvas, 94 x 142 cm. © Lerato Nkosi, courtesy Latitudes Online.

The Original Urge

Matthew Eguavoen on Jungle Justice (2020)

I created that particular piece here in Nigeria. I don’t know if it happens in other parts of Africa, but in Nigeria, we have something called Jungle Justice, wherein somebody can steal something as small as five nairas or ten nairas, and they can bond the person’s (petty/misdemeanor theft) personal life without justice, without taking the person to the police station, without any court cases, they just sub that justice there and then, while it happened. During that particular time, I was going through this emotional breakdown; I was kind of depressed. Because everything around me wasn’t going as planned, and 2020 was during the pandemic. And things were not really working for me. So it was at a point where I was kind of tired about everything, where it looked like nothing was working, and then everything around me at that particular time was just very depressing. I kind of imagined what the question would be going through my mind at that particular time if I were in that situation, and then they are being beaten mercilessly, and then petrol fell and all that. And it kind of resonated with how I felt at that particular time because I was depressed. So I just decided to put my all into the work.

Matthew Eguavoen, Jungle justice I, 2020, 72.4” x 61.4” (184cm x 156cm). © 2022 Matthew Eguavoen, Nigeria.

WonderBuhle on We No Longer Gonna Run (2021–2022)

Well, that work was created here in South Africa also around the pandemic, when it escalated to an unrest, and people were frustrated to know about certain resources that they couldn’t get. And then they started taking things and the looting and other things that happened. There were incidents that added to suffering, like racial segregation, and here in Durban, specifically, where it is more like a black-dominated city and also very Indian-dominated. So segregation started where some places were barricaded. I started to interview a few people that I know and some of my relatives who live in Phoenix about how they experienced this chaos, and there were many stories that I heard. I created a series which is called Phoenix Survivors because that was the main spot where the atrocity happened. So what do we stand for? How can we move the conversation further? What does it mean to also be involved in this violent exchange at this point where the country is preaching? I got very confused, and I started creating this piece. That’s why I saw this red color to just pull that fire. But at the same time, I wanted to have a sense of calmness with that pink because it looks amazing, but when you go inside, it’s boiling. The image making that you see, it’s really like a statement saying, “There’s no way to run; this is also my place. I have a right to defend myself in all kinds of ways whether you shoot me or not.”

WonderBuhle, We no longer gonna run, 2021-22, Acrylic and metallic paint, 87.79” x 130.31” (223cm x 331cm). © WonderBuhle 2020, courtesy BKhz Gallery, South Africa.

Annan Affotey on his ‘red eye’ portraits

I grew up in Ghana until I was twenty-eight years old, and all my life, I have seen people with such eyes, and some of their eyes are more like yellow. And I never questioned when I see such eyes because I know it is very normal. When I moved to the US, I made some friends, and whenever we went out to dance salsa, a random person would come to me and then start asking questions like, “hey, why are your eyes red?” Sometimes they don’t ask me directly, but to my friends, “why your friend’s eyes are red?” and other comments like I do drugs, I drink alcohol, and all of that. But I don’t do any of these things. Some of these questions I just ignore them. I never got questions like this when I was living in Ghana. When I started this new body of work, I was like, why don’t I put it in my pieces. It started in stages, it started with lighter colors, with white, and then as it went on, I started to enrich the color without even realizing it. I didn’t even realize it was turning red because I was telling a story about how I used to see myself until it was pointed out to me that my eyes were red. So that is how it started.

I’d like to say a few things that really make my work stand out and make people recognize my work. There are four elements that you can see in my paintings, the first is the red eyes, the second is their skin tone, the third is the texture that you see in my works—very thick applications, and then the last thing is the unpainted parts of my pieces. So talking about the unpainted hands, there are actually several things that I sometimes leave unpainted in my pieces, but the only thing that really draws viewers’ attention is that one unpainted hand. When my viewers ask me why did you leave one hand unpainted? I’m very happy about that question because it engages a conversation and it allows the viewer to be part of the painting. And that is why I don’t usually paint the whole thing.

Annan Affotey, Blending in (St Paul De Vence), 2022, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 84 x 72”. © 2022 Annan Affotey, courtesy DeBuck Gallery.

Lerato Nkosi on her series of work inspired by a book

My recent work is inspired by a book by Bell Hooks, All About Love. When I decide to work on a body of work, especially for competitions, I don’t like to over-create works for no purpose, so I always dedicate it to a specific book that I read. As I read through the book, I always have a journal to write down the words that stand out at that moment and what they symbolize within that context, then I investigate what they mean in my personal life and experience. I read All About Love by Bell Hooks because she speaks about philosophy and what feminism is on our daily basis—it’s not like toxic feminism; she speaks about how we as women also have the responsibility for everything that happens—and it’s so in line with what my work is about.

As for the book I’ve just started reading now, I have so many disagreements with it, but I manage to actually find words that strike me at the same time. It is crazy how disagreements can come with something valuable, like how it inspired my recent work Wounded Healing. This work is based on the novelistic idea of womanhood and the responsibility that women have in society. We have wounds, but yet we heal, we heal the children we are raising, and we heal people around us.

Lerato Nkosi, Wounded Healing, 2022, Ink and stamp on canvas, 124 x 94 cm. © Lerato Nkosi, courtesy Latitudes Online.

The Distanced Belonging

Annan Affotey

Dogs appear in several of my latest artworks. I love dogs. It was a one-time series that I did with Danny First during my art residency last year. Our relationship with dogs in Ghana is very different from people’s relationships with dogs in America. I have never seen a Ghanaian allowing their dog to be on the couch or sleep on the same bed with them. My relationship with dogs started when I was very young. I’ve always loved dogs growing up; when I was ten years old, I got a dog as a gift from my neighbor. The dog passed away at the age of four, and I couldn’t afford to get another dog. When I moved to the US, we convinced my in-laws to buy a dog, whose name is Coco. And I decided to tell a story about my past and my relationship with dogs through these pieces.

Annan Affotey, Diego First, 2021, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 72 x 60”. © 2021 Annan Affotey, courtesy Danny First.

WonderBuhle

When the motif of flowers started to show up in my work, I was in the UK back in 2018. I felt like something was missing from the work. I needed something that’s going to define the work more and show where I’m from and give a stronger representation of my home. So I started to work on small samples of material that I could use to give this work a full identity, and I started to think about my grandmother’s garden, where she had these flowers that she used to call “lucky flowers.” These flowers were planted amongst the sage for spiritual connections. Most of my work lives in the studio for shows and some collectors, but I wanted to give the work a sense of belonging. Every time I’m leaving home, like in my village, my grandmother’s house, they are always doing a small ceremony, whether it’s a prayer or it’s in the form of burning the sage itself, saying, “I wish you go well, you get protected along the way, and have a safe journey,” things like that. I wanted to communicate the same thing with my work. So I started to lay out these flowers from that point and charge the pieces with this energy of knowing home and having guidance.

Matthew Eguavoen

When I started painting officially, it was in 2018, then in 2020, I got better. The pandemic took a toll on me, I was depressed, and I needed something to take me out of that situation where I found myself. So painting was one thing that I persistently and continuously did at that particular time. I did my first solo show in April this year. It was about family and the bond that exists between two or more people. There were couples in strategic positions showing these emotions existing between the two of them, or three of them, in some of the works about family. So this was me trying to say that even though we have our differences as human beings, there is this bond that connects us as people, as human beings, something that we share, which is love; it doesn’t matter what color of our skin is.

Then, if you look at the eyes, the eyes are always really dark, brownish of some sort. I made the eyes really dark because I feel like every one of us has gone through different experiences. You don’t know what other people are going through. When you look at my work, you can’t really tell if they’re excited, if they are sad, or if they are worried. You just see them in a very still state. And that’s how all my mood is, something I kind of translate from my own life and then from the society where I find myself as a way of connecting the two of them.

My solo show coming up next month in London with PM/AM Gallery is about the migration of Africans, mostly Nigerians, to the UK, Canada, and the USA for greener pastures. The reason why they migrate is that they feel like the economy of Nigeria is very bad and the social security is not so good. It got me thinking if we all leave, who would do the job? Who would make all these things right? The places that Nigerians are going, be it the UK, Canada, or the USA, where some particular people have already done the work. They put all these things in place. So what are we doing as Africans if we just leave and go to a different country? What are we doing back home to change the status quo? Because if we don’t do anything and just keep leaving, it will get even worse. So that’s the story around the work I’m currently creating. I feel like it’s time to talk about this because we have a very high level of migration right now. I’m trying to see how I can stay in the conversation, to have people talking about this stance, and see what we can do differently even if we have to leave.

Matthew Eguavoen, I didn’t swim all the way because I enjoy it, 2022, 51.2” x 39.4” (130cm x 100cm). © 2022 Matthew Eguavoen, Nigeria.

WonderBuhle

I think the image-making behind the work comes from a collection of my own personal thoughts and experiences, but also, I’m very interested in people’s needs, and it becomes a combination of these two different spaces where I’m seeing life from the outside. I’m conscious about how I’m moving and experiencing my country at this point. What I’m painting is based on the current situation of what I’m living and what my people are living. As much as I understand that my pieces can sometimes be seen as figurative because they can have a lot of these mysterious forms imposed on them, there is also a part of the society that we learn and then recreate to move forward. So I think the work just carries that vision when the future generation visits the galleries or museums, they will see something that gives them information about what is going on during this time. Because I’m not shying away from what I see from my window and what I’m experiencing when I’m walking into the streets. They’re all reflections of the things that you see in my work, whether it’s beauty or social ills.

WonderBuhle, Media Lies, 2020, Acrylic and metallic paint, 39.37” x 39.37” (100cm x 100cm). ©WonderBuhle 2020, courtesy BKhz Gallery, South Africa.

The Asymmetrical Interest

Annan Affotey

I would say a collector that buys artwork because they love them. I know there are collectors who value and view art as financial assets, but I prefer a collector to buy the artwork because they love it, want to hang it, and not to put it in storage for the artist to make a name before they bring it out to sell it.

Some art advisers and galleries would have the collectors sign a five-year agreement that prohibits the selling of artworks during that period of time. However, sometimes that doesn’t work. I prefer to create a good relationship with the collector and believe in the collector that even if they want to sell the artworks, we can have a certain agreement.

Annan Affotey, Three of a Kind, 2022, acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 144 x 108” (12ft x 9ft). © 2022 Annan Affotey, courtesy Gallery 1957.

WonderBuhle

Once the work moves away from the studio, it just becomes more like a commodity. People have different ideas on how they look at it and how what they want to do with it. At this point, what I’m trying to prioritize and what we should prioritize is to protect the work. One of my friends said to me, “your work has been protecting you for the longest time; now it’s time for you to protect the work.” I really like that, and I live with that every day.

Matthew Eguavoen

To be in demand was something that I wanted. But it got to a point where it was overwhelming because my work takes time. Sometimes I have to spend two or three weeks thinking about something I want to put on canvas for one hour because I have to put a lot of thoughts into it. I wasn’t producing as fast as the demand was growing, but then I got comfortable with it. I feel like the world can wait, I know what I want to create, and I know the issues I want to use my work to address. Let the interest be there, but as much as the interest for my work is there, I want to use my work as a medium to deliver a message. I want the context behind my work. So that’s how I was able to take myself away from the overwhelmingness of creating and just create.

Annan Affotey

It has been very crazy since last year. My first solo show in Los Angeles was when everything started. It was becoming too much for me. My wife used to help me with the emails, and it was also becoming too much for her because she’s a full-time student at Oxford University. So we had to hire a manager because I just want to paint, I just want to concentrate on my artwork. Like Matthew said, the world can wait, and it is very true. If you really want the art, you have to wait because we don’t want to just create anything.

WonderBuhle

I really didn’t take it to the head because just like what Matthew was saying, I paint at my own pace. At some point, it can be very overwhelming, and it can also be very exciting. It just comes with different emotions. I think the best thing to do is not to think like that and paint at a different pace because it might harm the process of your creation when you’re trying to fit them into the market; it might look like you are just painting to make money.

WonderBuhle, Alindelwe, 2022, Acrylic and metallic paint, 63 × 51.2” (60cm × 130 cm). © WonderBuhle 2020, courtesy of Galerie Ron Mandos, Netherlands.

WonderBuhle, iSbonakaliso, 2022, Acrylic and metallic paint, 86.6 × 55.1” (220cm × 140 cm). © WonderBuhle 2020, courtesy of Galerie Ron Mandos, Netherlands.

Interview by Makgati Molebatsi. Curated by Murphy Guo.

This story was published in noisé 02 A Falling Leaf Heralds Autumn, 2022.